Gemmology, a complex business | EN

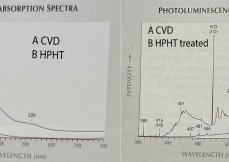

Gemmology encompasses a multitude of areas of knowledge ranging from geology to chemistry. Devices that were once used to analyse stones are now obsolete thanks to technological advantages in synthesis.

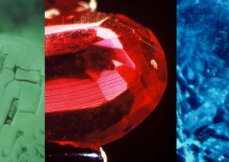

« The testing of all diamonds is done on the block, and they withstand the blows so well that the iron bursts and the block itself bounces.» These words are from the natural history of the Ancient Pliny who died on 24th August AD79 during the Vesuvius volcano eruption - book XXXVII (37), 57. In the wake of this sad text, thousands and thousands of carats have been destroyed forever in the course of explorations and conquests as history rolled on. The diamond is in fact the natural product that is most resistant to usage - a hardness rating of 10 - but not to shock. It has a crystallisation within the cubic system with a perfect cleavage, and this is the principle of the first stage of cutting a stone - cleaving, cutting, rough cutting, cross-shaping and brightening. For this reason, a cut diamond is fragile at the neck - the point under the stone - and on its girdle - the circumference of the stone where the setter places the clamp hooks. During the Middle Ages, diamond fraud was all about imitation stones: topaz stones or colourless zircons or more simply glass. Coloured glass was used to imitate rubies, sapphires and emeralds. On the city walls of Anvers during this period there was a notice forbidding any trade in imitation diamonds, rubies, sapphires, emeralds and spinel. A fine of 25 deniers was imposed to punish fraudsters: a third went to the city, a third to the Lord above - the Church - and a third to the person denouncing the fraudster. This law protected the consumer from crooks and it is to be regretted that it was abolished.

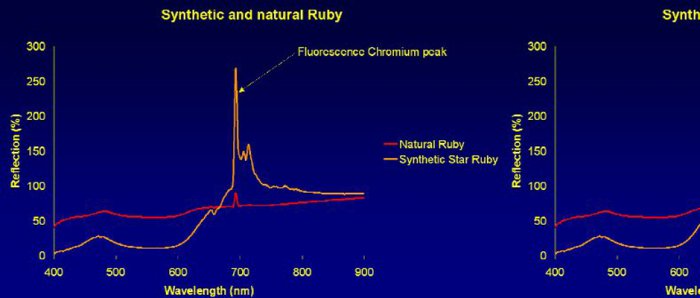

During the 18th Century, the first imitation to approach the lustre of a diamond came onto the scene: Strass, which was no more than glass whose surface was coated with the same product as were mirrors. This imitation continues to be used in whimsical jewellery. But viewed through a magnifying glass and even to the naked eye, it is easily identified. The first synthetic material appeared at the end of the 19th Century: the Geneva ruby, which created a panic in the precious stones industry. Contemporary newspapers began to talk of the end of the ruby and of the definitive collapse of its value. Today natural rubies that have not been heated are fetching fantastic prices in the trade market and other prestigious sales venues. Using this technique that was discovered by Verneuil, a good number of other synthetic products flooded the market. Manufacturers from France, America, Japan and Russia improved their techniques throughout the 20th Century, creating better and better imitations of natural products. And yet the genuine jewellery trade has never been keen on these synthetic products, as the consumer rightly wants a natural stone, even if it is smaller. However, someone who buys a synthetic stone knowing that they are doing so and paying a lower price is perfectly free to do so.

|